The Buffalo Nickel and Bison Facts Today

Clip: 10/17/2023 | 9m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

The 1913 Buffalo Nickel raises important questions how we think of the American West.

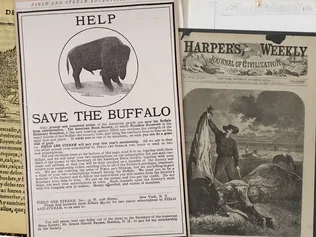

The 1913 Buffalo Nickel raises important questions about the romanticization of the American West. Bison were brought back from the brink of extinction. Today conservation work continues in concert with the people whose lives have been intertwined with the buffalo for over 10,000 years. At least 80 tribes in 20 states control their own herds on nearly a million acres of tribal land.

Corporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...

The Buffalo Nickel and Bison Facts Today

Clip: 10/17/2023 | 9m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

The 1913 Buffalo Nickel raises important questions about the romanticization of the American West. Bison were brought back from the brink of extinction. Today conservation work continues in concert with the people whose lives have been intertwined with the buffalo for over 10,000 years. At least 80 tribes in 20 states control their own herds on nearly a million acres of tribal land.

How to Watch The American Buffalo

The American Buffalo is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipNarrator: In 1913, the United States came out with a new design for the nickel, done by the sculptor James Earle Fraser.

Fraser said he wanted a coin "that could not be mistaken for any other country's coin."

On one side, the new nickel showed the profile of an American Indian.

On the other was an American buffalo, modeled after a bison Fraser saw in New York City's Central Park Menagerie.

Rinella: We know its name.

It was called "Black Diamond."

And it lived in a cage.

And he uses it as his model.

And it was sold to a butcher.

And the model for the buffalo head nickel was processed and parted out and sold as meat in the Meatpacking District in Manhattan.

And it opens up this idea of just how conflicted the symbol is.

We look at it and we see a symbol of wilderness and a symbol of the wanton destruction of wilderness.

Horse Capture, Jr.: You look at that old nickel, there's a buffalo.

At one time, they almost wiped them to extinction.

Why did the European put that buffalo on that nickel?

Was it just a curiosity, or was it something that kind of meant something to them in an odd way?

So, in my confusion, and my need to understand, is...do you... have to destroy the things you love?

♪ Narrator: By 1933, the American Bison Society reported that 4,404 buffalo existed in 121 herds in 41 different states.

Half of them were grazing in now 9 government-protected herds.

Compared to the millions of buffalo that had once covered the Plains, those were tiny numbers; but enough--and in enough different places-- that the Bison Society began making plans to disband, declaring that the American buffalo was finally safe from extinction.

♪ This Society was successful, but their understanding of the problem was really short-sighted.

They didn't know about ecosystems.

They thought, if you got a buffalo, you've saved him.

That's not it.

You got to save their habitat.

♪ Narrator: That same spring of 1933, 75 calves were born on the National Bison Range in Montana.

One of them, a little bull, had blue eyes and white hair-- a genetic rarity.

A white buffalo is so sacred and so full of hope and goodwill for the tribes.

Just a huge blessing.

It was a tremendous gift from Creator.

♪ Narrator: The staff at the Bison Range called the little bull "Whitey" at first-- and its presence turned the preserve into a tourist attraction for a while.

But to the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles on the Flathead Reservation-- and to virtually all other Native tribes-- a white buffalo was more than a statistical oddity.

It had special spiritual power and sacred meaning.

It was considered "big medicine"-- and that became his name.

Pablo: I was 3 years old.

My grandpa and my dad took me to the bison range and wanted me to touch him.

He was so old; he stood inside this fence and he didn't move.

I touched him and I thought he would be soft, his head, like my teddy bear.

And it was bristly.

And that was my first impression, was he's big and I love his eyes and he's bristly.

♪ Dant: The story of the American buffalo is a cautionary tale.

It's a lesson in how to live sustainably with nature.

We didn't do a very good job.

We almost screwed it up.

But we didn't, and, so, there's hope.

It's a possibility of what could come.

Flores: You don't get a lot of chances to correct history's mistakes.

You get a few.

And when you get them, you damn sure better take advantage of them.

I think we've got an opportunity to do this with buffalo.

And, if we do, I think America can look back on its history and say, "We got wise."

♪ Pablo: You're supposed to make decisions that go 7 generations beyond you.

But we aren't looking at the future.

We're looking at right now.

And that's not far enough.

She's all we have, this Earth.

And we destroy that, we're destroying ourselves.

And we just don't get it.

♪ Narrator: The American buffalo had been brought back from the brink of disappearing forever.

But its story is unfinished and still being written, taking new turns, facing new challenges, and offering more lessons yet to be learned.

Being saved from extinction is not the same as being wild and free.

Today, the United States is home to more than 350,000 bison.

Native peoples oversee 20,000 of them.

20,000 more are protected in federal and state preserves.

But the rest exist in private herds, many of them confined like cattle, fattened in feed lots, raised for slaughter.

Jenkinson: Until buffalo can move, more or less, at will, over a vast grassland, we haven't restored them at all.

We've made them a very special grass-eating zoo creature.

But to turn them loose in-- in the way that they were meant to be, the way they were when Lewis and Clark came through, when Plains Indians were flourishing, it's a dream that I thought would never happen and it--and it's probably going to happen.

Narrator: Some ranchers and many non-profit organizations-- including the Nature Conservancy, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and American Prairie-- have committed to providing their buffalo with more room to roam and native grasses to eat-- something closer to the habitats they once knew.

Even the American Bison Society has been revived.

♪ It's going to be a big job, but if, if human beings are... think they're the best animal in the world, now is our chance to prove it.

Narrator: The most important work of restoring bison to their homelands is being done in concert with the people whose lives have been intertwined with the buffalo for more than 10,000 years.

Back in 1991, representatives from 19 tribes gathered in the Black Hills to begin to form the Intertribal Buffalo Council and organize attempts to bring some of the bison from Yellowstone and other federal preserves back to their reservations.

It was an act of healing that would re-establish a sacred connection with the buffalo that had been broken for more than a century.

An elderly Lakota woman took one of the founders aside.

"It's best you ask the buffalo if they want to come back," she said, so, the group held a ceremony to do exactly that.

"They said they wanted to come back," the man remembered, "but they said they didn't want to come back as cows.

They wanted to be buffalo.

They wanted to be wild again."

Now, at least 80 tribes in 20 states control their own herds, grazing on nearly a million acres of tribal land.

And on the Flathead Reservation, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes have taken over management of the National Bison Range.

Buffalo Bill and His Wild West Show

Video has Closed Captions

By 1889, Buffalo Bill Cody was the most famous American in the world. (5m 23s)

George Bird Grinnell and Early Conservation Efforts

Video has Closed Captions

Grinnell fought the destruction of birds and other wildlife, including the buffalo. (6m 25s)

Sitting Bull and the Wounded Knee Massacre

Video has Closed Captions

More than 250 Lakotas – mostly women and children – were killed by U.S. soldiers. (6m 21s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipCorporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...