George Bird Grinnell and Early Conservation Efforts

Clip: 10/17/2023 | 6m 25sVideo has Closed Captions

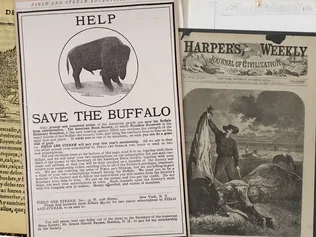

Grinnell fought the destruction of birds and other wildlife, including the buffalo.

George Bird Grinnell was a student of Lucy Audubon, the widow of the famous ornithologist and painter. She taught him how to observe and appreciate the natural world. More importantly, Lucy taught him to think about future generations and how they might live one day. Grinnell put Lucy’s lessons to work, fighting against the destruction of birds and other wildlife, including the buffalo.

Corporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...

George Bird Grinnell and Early Conservation Efforts

Clip: 10/17/2023 | 6m 25sVideo has Closed Captions

George Bird Grinnell was a student of Lucy Audubon, the widow of the famous ornithologist and painter. She taught him how to observe and appreciate the natural world. More importantly, Lucy taught him to think about future generations and how they might live one day. Grinnell put Lucy’s lessons to work, fighting against the destruction of birds and other wildlife, including the buffalo.

How to Watch The American Buffalo

The American Buffalo is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ Narrator: Growing up in New York City, George Bird Grinnell had been a student of Lucy Audubon, the widow of the famous ornithologist and painter.

Among the things she taught the boy was how to observe and appreciate the natural world.

Man: But, even more significantly, she teaches him about an ethic that was important to her that she called "self-denial."

And what she really meant by self-denial was the notion that you would, uh, you would think about future generations, that you would not do things that you might want to do in deference to thinking about, uh, how your children and grandchildren might live one day.

And that ethic runs almost directly counter to the prevailing norms of the day.

Narrator: As the editor of "Forest and Stream" magazine, Grinnell put Lucy Audubon's lessons to work.

He railed against the hat-making industry, which had created a fashion frenzy for the colorful plumes of birds in the Everglades, threatening the survival of egrets and ibises.

[Gunshot] And he decried the market hunters who were supplying restaurants with the meat of passenger pigeons, driving a bird that once existed in the billions toward oblivion.

To help him carry on the fight against this commercial destruction of bird life, Grinnell founded an organization named in honor of his mentor and her husband: the Audubon Society.

But he never lost his focus on the American buffalo.

♪ Punke: Every saloon in America wants to have a stuffed buffalo head to hang on the wall.

And the market for buffalo heads goes through the roof.

And, uh, what used to be a $4.00 shot if you killed a buffalo and could sell its hide becomes a $500 shot.

And the response to that is poachers descend upon these few places where there still are buffalo remaining and try to kill them.

Narrator: By 1894, the last surviving herd of free-ranging bison in America could be found in Yellowstone National Park.

But the superintendent reported that poachers had killed 114 of the 200 William T. Hornaday had estimated were there only 4 years earlier.

The Army was responsible for stopping poachers in Yellowstone and for enforcing regulations against vandalizing the geyser formations, but the park existed in a legal no-man's land, with no federal law giving the soldiers clear authority to prosecute offenders.

Their only recourse was a warning, or in the most serious cases, temporary expulsion from the park.

No one understood the threat to Yellowstone and its wildlife more keenly than George Bird Grinnell.

Punke: He knows that it's this vast place.

He knows that there are a handful of wild buffalo who are still there because theyve been far enough away from the railroads that they still survive.

Grinnell realizes that this is the buffalo's, that Yellowstone is the buffalo's last chance.

[Gunfire] Narrator: On March 13th, 1894, two troopers out on patrol in a remote corner of Yellowstone heard shots in the distance.

They hurried in that direction and soon came across several buffalo carcasses.

A man was hunched over one of them, so busily skinning it that he didn't realize anyone was there until a soldier was beside him with a drawn gun.

The poacher was Edgar Howell, who had been killing Yellowstone's bison for years.

As luck would have it, a reporter named Emerson Hough, on assignment for Grinnell's "Forest and Stream" magazine, was also in the park-- with a photographer-- to write an article about Yellowstone in the winter.

When the poacher bragged that the worst punishment he could receive for his crime was expulsion from the park, Hough realized he had stumbled onto a great story and quickly telegraphed it to Grinnell in New York City.

Grinnell knew just what to do with it-- and began to generate a public outcry for Congressional action through a series of stories, along with photographs that included soldiers posing with 9 buffalo heads that Howell had not yet hauled out of the park.

Punke: And it's a political lightning bolt in Washington.

In his editorials, Grinnell was very good at explaining that Yellowstone National Park belongs to all Americans.

So that when someone, when a poacher, is stealing from Yellowstone National Park, he's stealing from you.

Narrator: In Washington, Grinnell's friend Theodore Roosevelt, now a Civil Service Commissioner, sprang into action.

He stalked the corridors of the Capitol, lobbying for a bill that would institute fines of up to $1,000 and jail sentences of up to two years for offenders.

On May 7th, 1894-- less than two months after Howell's capture-- President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law, authorizing regulations that would protect the park, its geysers, and its wildlife-- at least on paper.

Buffalo Bill and His Wild West Show

Video has Closed Captions

By 1889, Buffalo Bill Cody was the most famous American in the world. (5m 23s)

The Buffalo Nickel and Bison Facts Today

Video has Closed Captions

The 1913 Buffalo Nickel raises important questions how we think of the American West. (9m 15s)

Sitting Bull and the Wounded Knee Massacre

Video has Closed Captions

More than 250 Lakotas – mostly women and children – were killed by U.S. soldiers. (6m 21s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipCorporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...