Into the Storm

10/16/2023 | 1h 59m 4sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

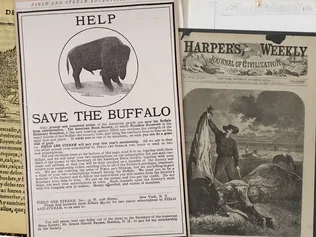

An unlikely collection of Americans rescues the national mammal from extinction.

By the late 1880s, the buffalo that once numbered in the tens of millions is teetering on the brink of extinction. But a diverse and unlikely collection of Americans start a movement that rescues the national mammal from disappearing forever. In English audio with captions, Spanish audio with captions, and Descriptive Audio.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADCorporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...

Into the Storm

10/16/2023 | 1h 59m 4sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

By the late 1880s, the buffalo that once numbered in the tens of millions is teetering on the brink of extinction. But a diverse and unlikely collection of Americans start a movement that rescues the national mammal from disappearing forever. In English audio with captions, Spanish audio with captions, and Descriptive Audio.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADHow to Watch The American Buffalo

The American Buffalo is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipAnnouncer: Major funding for "The American Buffalo" was provided by the Better Angels Society and its members; the Margaret A. Cargill Foundation Fund at the Saint Paul & Minnesota Foundation; Diane and Hal Brierley; the Keith Campbell Foundation for the Environment; John and Catherine Debs; Kissick Family Foundation; Fred and Donna Seigel; by Jacqueline Mars, John and Leslie McQuown, and Mr. and Mrs. Paul Tudor Jones.

Funding was also provided by the Volgenau Foundation and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

♪ Announcer: Stories hold the power to draw us together and shape our tomorrow.

If we're courageous enough to look, lessons are written in our history.

♪ ♪ ♪ Man: Gentlemen, why in heaven's name this haste?

You have time enough.

Why sacrifice the present to the future, fancying that you will be happier when your fields teem with wealth and your cities with people?

In Europe we have cities wealthier and more populous than yours and we are not happy.

You dream of your posterity; but your posterity will look back to yours as the golden age, and envy those who first burst into this silent, splendid Nature, who first lifted up their axes upon these tall trees and lined these waters with busy wharves.

Why, then, seek to complete in a few decades what took the other nations of the world thousands of years?

Why, in your hurry to subdue and utilize Nature, squander her splendid gifts?

You have opportunities such as mankind has never had before, and may never have again.

Lord James Bryce.

♪ Different man: The first time I met a buffalo, I looked into his eyes, and it was like looking into the past and the future at the same time.

Because I really do think that they have seen the whole tragedy that has played out on the Great Plains.

I think that one of the ways they survive, and have survived for hundreds of thousands of years, is they turn into the wind and they move through the storm rather than being chased by the storm.

Different man: They say, in a bad storm, he has to turn and face that storm or else things won't be good for him.

I heard that, that saying, but as I start looking at them, then it... that saying made sense to me.

Like, you're right.

If you don't face the day, you don't face the storm, there could be problems.

♪ Different man: The creature of the American West was the bison.

The minute you see one, you understand it.

Their sheer magnificence.

Their confidence; they're unafraid.

They're massive, but they can run 35 miles per hour.

And, somehow, they're the symbol of America, with a capital "A."

And to think that our Indian policy and our greed and our industrialization would just blink this thing out and we would just say, "Well, that was then and this is now."

That seems like a repudiation, somehow, of the very idea of America.

♪ Different man: We are the most dangerous species of life on the planet, and every other species, even the Earth itself, has cause to fear our power to exterminate.

But we are also the only species which, when it chooses to do so, will go to great effort to save what it might destroy.

Wallace Stegner.

♪ Narrator: By the early 1880s, the buffalo that had once teemed across the Great Plains by the tens of millions had been reduced to fewer than 1,000, scattered in small, isolated herds-- victims of a decades-long frenzy of slaughter that stripped them of their hides and left their carcasses to rot in the sun.

Most people believed the continent's most magnificent creature was about to disappear forever.

During the same time, Native Americans had been dispossessed of most of their homelands, confined to reservations, and deprived of an animal that had fed their bodies and nourished their spirits for untold generations.

Some thought the Indians, too, had become what they called a "vanishing race."

♪ But as the nineteenth century ended, an unlikely group of Americans would begin to try, somehow, to pull the buffalo back from the brink.

♪ Man: And the road back begins in all these little different places, with these different characters, with their own reasons.

Some of them actually odious.

It's unorganized at first, and, then, slowly, it finally has to gain enough momentum that the, those individual efforts can coalesce and become something that might save the national mammal from just becoming a memory.

The early history of the modern conservation movement is full of people who did the right thing for the wrong reasons.

Many of the people who wanted to save the bison were motivated by reasons that were all wrapped up with nationalism, with racism, and their own ideas about who they were and what the nation should be... and then there were people who genuinely loved these species and wanted to see them survive.

Man: There were a lot of things contributing to the near extinction of that bison.

But what that also means is that many things had to contribute to the preservation of the bison from extinction.

We can say that were it not for these people, with their particular motivations, the bison might well have gone extinct.

♪ Narrator: An ambitious taxidermist in the nation's capital, who initially hoped to kill some of the remaining buffaloes for preservation as museum exhibits, would join forces with an earnest New Englander whose personal passion for bison would grow into a campaign for a national movement to protect them.

A former hide hunter would switch from shooting bison to breeding them; and a flamboyant former cavalry scout, who had once killed thousands of buffalo, would begin saving them-- and then bring them to the world in performances that thrilled millions.

The wife of a Texas cattleman and former Indian fighter would persuade her hard-bitten husband to take pity on some buffalo calves.

It would eventually lead him to reconsider his relationship with the animals and the people he had once despised.

On two different Indian reservations-- one in South Dakota, the other in western Montana-- families would start small herds that would become the largest in the nation.

A patrician New York magazine publisher, whose experiences in the West had turned him into a crusading conservationist, would befriend an energetic, impetuous hunter-- and convert him to the cause, which he would take with him all the way to the White House.

And a Comanche leader, who had once waged war against the hide hunters, would become a man of peace-- and live to see the buffalo return to his homeland.

Man: I know there is such strength and resilience to where this is not just a story of tragedy; this is a story of persevering and continuing on.

Helping to bring these buffalo back.

♪ Narrator: In the fall of 1883, a young politician, the eldest son of a prominent New York City family, became alarmed by reports that the vast herds of buffalo were quickly disappearing from the Great Plains.

So, he hurried west on the Northern Pacific Railroad and got off when he reached the Little Missouri River in the heart of the Badlands in Dakota Territory.

[Train whistle blows] He was 24 years old, and he feared that the bison would all be gone before he got the chance to shoot one.

His name was Theodore Roosevelt.

Jenkinson: He hires a local guide, Joe Ferris, who's very reluctant to take this New York "dude" out buffalo hunting.

For one thing, there are no buffalo.

And he keeps saying to Roosevelt, "This...you're not going to probably find one."

And it's raining and chilly and cold, and everything goes wrong.

Roosevelt falls off his horse into a patch of prickly pear cactus and his gun snaps up and opens a vein in his forehead, and blood is shooting out.

Everything goes wrong that can.

Duncan: He wounded a buffalo, after he finally found some, but it got away.

The next day, he sees one and he had a clean miss, didn't even hit him.

They were living on cold biscuits.

Their horses get stampeded by wolves.

It's just miserable.

He woke up, one of those mornings, uh, and Joe Ferris said... he woke up and looked around at this wet and cold, and says, "By Godfrey, but this is fun."

Narrator: Finally, after 3 days of scouring the Badlands, they encountered a big bull.

[Gunshot] This time, Roosevelt brought it down.

♪ He immediately took a $100 bill out of his pocket and gave it to Joe Ferris, his guide, and then he did an "Indian War Whoop dance" around the carcass.

They cut out steaks.

They cut off the big, shaggy head and--and then had it mounted by a taxidermist in Bismarck.

Narrator: Before heading home, Roosevelt impulsively invested some of his inheritance in one of the many cattle ranches sprouting up on the former buffalo range.

He would return off and on for the next 4 years to pursue what he called "the strenuous life" and to escape the grief he suffered when his wife and mother died on the same day.

"Black Care," he said, "rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough."

Roosevelt would eventually write a book about his experiences.

In it, he declared that he had become "at heart as much a Westerner as I am an Easterner."

♪ Man as Roosevelt: While the slaughter of the buffalo has been in places needless and brutal, and while it is to be greatly regretted that the species is likely to become extinct, it must be remembered that its destruction was the condition necessary for the advance of White civilization in the West.

Above all, the extermination of the buffalo was the only way of solving the Indian question... and its disappearance was the only method of forcing them to at least partially abandon their savage mode of life.

From the standpoint of humanity at large, the extermination of the buffalo has been a blessing.

♪ Man: We are sorry to see that a number of hunting myths are given as fact, but it was after all scarcely to be expected that with the author's limited experience he could sift the wheat from the chaff and distinguish the true from the false.

George Bird Grinnell.

♪ Narrator: When George Bird Grinnell, the publisher of "Forest and Stream" magazine, gave Theodore Roosevelt's book a mildly critical review, the author burst into Grinnell's office to complain.

The two men turned the awkward moment into the beginning of a lasting friendship.

They both quickly realized they shared much in common, including a love of the West and its big game animals.

Duncan: Roosevelt had two buffalo trophy heads on the wall at his home in Sagamore Hill.

In Grinnell's office, he had two buffalo skulls.

And he wrote about them and their presence in his office, and what that evoked in him.

It reminded him of the death of the bison and what that meant.

Not a trophy.

A reminder.

Narrator: Together, Roosevelt and Grinnell formed the Boone and Crockett Club to promote what they called "the manly sport" of hunting, and at its first meeting, elected Theodore Roosevelt its first president.

Nijhuis: To these men, there was no contradiction between their concern for conservation and their love of hunting.

They wanted to protect these species because they wanted to continue hunting them.

At the end of the 19th century, there are a lot of men who are terribly concerned that this increasingly urban and comfortable and cosmopolitan American society is pampering American men and making them too soft.

And, so, what American men need to do is they need to experience the frontier.

Nijhuis: Roosevelt wanted to preserve what he saw as these American ideals.

He wanted to preserve it in order to protect his own ideas about national progress, about White masculinity, about his own race.

♪ Narrator: At the same time it promoted sports hunting, the Boone and Crockett Club dedicated itself to "the preservation of the large game of this country" and called for strict regulations against the rampant market hunting laying waste to so many species.

Through his friendship with Grinnell, Roosevelt was beginning to broaden his view about Americans' responsibilities toward wildlife-- including the buffalo.

Man: Those guys first started introducing the idea that we have to operate with restraint.

And that was a revolutionary idea.

This idea that we have wildlife that is owned by the public.

Like, the American people own wildlife.

And the government, state and federal governments, help regulate it on our behalf, but it's our thing.

♪ Narrator: Meanwhile, in 1886, a onetime hide hunter named Charles Jesse "Buffalo" Jones left his home near Garden City, Kansas, and headed southwest toward the Texas Panhandle, where 10 years earlier he had taken part in the wholesale slaughter of the buffalo herds on the southern Plains.

The trip brought back painful memories.

[Gunshot] Man as Jones: Often while hunting these animals as a business, I fully realized the cruelty of slaying the poor creatures.

Many times did I "swear off," and would promise myself to break my gun over a wagon wheel when I got back to camp.

[Gunshot] The next morning, I would hear the guns of other hunters booming in all directions, and would say to myself that even if I did not kill any more, the buffalo would soon all be killed anyway.

Again, I would shoulder my rifle, to repeat the previous day's murder.

[Gunshot] I am positive it was the wickedness committed in killing so many that impelled me to take measures for perpetuating the race which I had helped to almost destroy.

Rinella: Did he have a radical transformation?

Maybe.

I do believe, though, he had a legitimate love for the animals.

But he was also--he had a love for the dollar.

Narrator: When a fierce winter devastated the cattle herds on the Plains, Jones remembered seeing buffalo unfazed by similar weather.

Man as Jones: I thought to myself, "Why not domesticate "this wonderful beast which can endure such a blizzard?

"Why not infuse this hardy blood into our native cattle and have a perfect animal?"

♪ Narrator: Once he got to Texas, Jones managed to locate and lasso 18 calves to bring back to Garden City, Kansas.

He purchased more from a private herd in Canada and made more trips back to Texas.

Then he began experimenting, crossing buffalo bulls with domestic cows, to create what he called "cattalo."

The results were mixed, at best.

Too many cows died in calving; too many calves were stillborn or sterile to make it commercially profitable.

But Buffalo Jones would have much better success-- and a greater impact on the future of the species-- by selling his bison to zoos and wealthy families interested in having their own private herds.

I really like the fact that Buffalo Jones was willing to accept his own responsibility.

He confronted his culpability and took on himself the responsibility of trying to save the animals that he had almost obliterated.

♪ Narrator: In early 1886-- the same year Buffalo Jones had gone to Texas to try to save some bison calves-- the chief taxidermist of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington was asked by the museum's director to make an inventory of the collection of bison skins and skeletons in storage.

William T. Hornaday quickly reported back that they didn't have much-- and all of it was in poor condition.

At age 32, Hornaday had already gained a reputation among his colleagues for impatience and arrogance, but he had also distinguished himself as someone who could hunt down and kill exotic species-- like elephants, crocodiles, Bengal tigers-- preserving them for display in museums.

Now he set his sights on the American buffalo.

Nijhuis: He wrote to people, all over the Plains and said, "Where can I find bison hides?

Bison skulls?

Our collection needs them."

And all of his contacts wrote back and said, "Good luck.

There are no more bison."

And, for Hornaday, this came as a real shock.

He described it as a "hammer blow to the head."

A species that to him, and to many other people, defined the nation, was so rare that the Smithsonian Institution, the most prominent museum in the country, couldn't get hold of a skull or a hide at any price.

Narrator: But one of his correspondents had alerted Hornaday that a few bison had been spotted between the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, so he immediately took the train to Miles City, Montana, in hopes that he could kill some for the museum.

Hornaday was soon crossing the rugged landscape near the Missouri River Breaks, still strewn with what he called the "ghastly monuments of slaughter," and after two weeks of fruitless searching, his party encountered a few buffalo.

They shot one old bull, but Hornaday considered it unsuitable for display because most of its fur had already been shed in the late spring.

They did manage to capture a small calf, which Hornaday named "Sandy," and brought back--alive-- to the Smithsonian, where it became a public attraction.

He was back in Montana by September, when whatever bison he could find would have full winter coats.

After two months, he and his crew finally found and killed more than 20 specimens, including one gigantic bull.

In its body, Hornaday found 4 bullets from previous hunters.

♪ Man as Hornaday: Under different circumstances, nothing could have induced me to engage in such a mean, cruel, and utterly heartless enterprise as the hunting down of the last representatives of a vanishing race.

But there is no alternative.

Perhaps you think a wild animal has no soul, but let me tell you it has.

Its skin is its soul, and when mounted by skillful hands, it becomes comparatively immortal.

[Gunshot] Narrator: When another bull was shot just before sunset, more than 8 miles from their camp, they decided to leave it for the night.

When they returned the next day, they found the carcass stripped not only of its hide, but also its flesh and tongue.

The head was untouched, except one side was painted yellow and the other painted red.

Jenkinson: And Hornaday falls into a fit of anger.

"They--they've desecrated my buffalo.

They--they've spoiled it."

And he, he thinks it's vandalism.

[Laughs] It's not vandalism.

It's probably the Crow; it might be the Blackfeet.

It could be Sioux.

But Natives have come and they have harvested the meat, which he wasn't going to do.

Uh, they've taken the hide for their own uses.

And then they have done the most important thing, which is to bow, in a sacred way, to this creature by painting it and positioning the skull.

It's a sacred thing that they've done.

And he's pissed off because they stole his specimen?

And he misses the lesson.

Flores: An animal whose head is painted like that, among some Native peoples, symbolizes an ending of things, a transition from one moment in time to another one.

As the Crow leader, Plenty Coups, put it when he saw that the buffalo were gone, as far as he was concerned, nothing else happened in history.

That was the end of history.

Duncan: This part of Montana was the same area where Lewis and Clark, in 1805, had seen so many buffalo that Lewis reported the men had to throw sticks and stones at them, just to get them out of the way.

This was the same place where, 5, 6 years before, the hide hunters had shown up, and a hide hunter could kill 22 buffalo in a morning's work.

And it takes Hornaday more than two months to find and shoot 22 buffalo.

That's the trajectory that the bison had been on.

Narrator: Back at the Smithsonian, Hornaday eagerly started work on a new way of displaying his specimens.

He would place 6 of them in a group: the huge bull he had killed, a younger bull, a yearling, two cows-- and the little calf, Sandy, who had died in captivity.

All of them were gathered around a small alkaline watering hole near some clusters of sagebrush, buffalo grass, and prickly pear cactus Hornaday had brought back from Montana.

They would be enclosed in the largest display case ever made for the museum: a glass cube that would allow visitors to view them from all sides.

As a taxidermist, he considered it his masterpiece and hoped his display would help galvanize the public against the final extermination of bison in North America.

He now blamed their destruction on what he called "man's reckless greed."

He also believed that it had gone unchecked because of the apathy of average Americans.

His new mission was to change that.

♪ Nijhuis: It was displayed at the Smithsonian for 70 years.

People lined up to see it and it was extremely popular.

It allowed people to get closer to a bison.

They were able to see how large these full-grown bison were in comparison to themselves.

They were able to get a sense of these animals as--as living beings.

Man as Hornaday: Probably never before in the history of the world, until civilized man came in contact with the buffalo, did whole armies of men march out in true military style... and make war on wild animals.

Its record is a disgrace to the American people in general, and the Territorial, State, and General Government in particular.

It will cause succeeding generations to regard us as being possessed of cruelty and greed.

♪ Narrator: In 1889, Hornaday created a map showing how the buffaloes' range had steadily collapsed, and he estimated that there were now 541 bison-- 256 living in a few zoos or private herds, about 200 in Yellowstone National Park, and only 85 roaming free and unprotected on the Plains.

It was all part of a much larger pattern of destruction that had reached a crescendo in the last decades.

"Here," Hornaday wrote, "is an inexorable law of Nature "to which there are no exceptions: "no wild species of bird, mammal, reptile, or fish can withstand exploitation for commercial purposes."

And he said it was this "Inexorable law that "any animal that got commodified by the market couldn't survive it."

And [laughs] he was pretty right about that.

Hornaday's idea was that if we're going to conserve some of these animals, we're going to have to protect them from the market.

Narrator: Hornaday sarcastically noted that Montana had recently passed a law against killing bison-- 10 years after they had been slaughtered-- and predicted that Texas might do likewise, now that the buffalo there had also been eradicated.

Nijhuis: After the success of his bison display, he started to think bigger.

The next step, he thought, would be to begin to raise bison in captivity.

Narrator: Hornaday persuaded the Smithsonian to start a small zoo on its grounds.

It included some deer, prairie dogs, bears, along with 4 bison that had been captured in the Black Hills.

The attraction proved immensely popular, and Hornaday began pushing for a more spacious location than the lawn of the Smithsonian.

With Congressional approval, he scouted the Rock Creek Park area of Washington and selected a site for what he hoped would be a proper national zoo.

♪ Woman: I cannot think of much of anything but the possibility of doing something great with the buffaloes for humanity.

My dream is a home for my little pets, to let them roam at will with plenty of room for a long time.

Molly Goodnight.

♪ Narrator: After her parents died, Molly Dyer had singlehandedly raised her younger brothers and then married Charlie Goodnight, who was already a legend in Texas.

He had been an Indian fighter with the Texas Rangers, blazed some of the early cattle trails north to the railroads, and then established the first ranch in the Palo Duro Canyon.

A cattleman, Goodnight had little sympathy for buffalo; he had paid to have the buffalo in the canyon killed so they wouldn't compete with his cattle for the grass.

Horse Capture, Jr.: Let's get rid of the buffalo so my cows can run here.

My cows.

Not this, what's free for the taking for all of us.

But "my," so I can make money.

And it's odd to get rid of something that everybody could enjoy to eat just for "my," the ownership of a livestock.

I can't even comprehend that.

I don't know if...there is an Indian alive, or was alive, that could comprehend that.

It seemed like a lack of ability to enjoy what the Creator made.

♪ Narrator: In 1878, Goodnight had sent some of his cowboys to drive the remaining bison out of the canyon and shoot any stragglers.

Molly, one of them remembered, "put a stop to the whole thing."

She felt sorry for the buffalo, considered them worth preserving as part of the region's history, and asked her husband to find a few calves she could nurture around the ranch house and keep her company.

Her closest neighbor was 75 miles away.

"I was not very enthusiastic over the suggestion," Charlie admitted, but he went out and roped a bull calf and a young female bison anyway and brought them in for her.

♪ By 1889, the Goodnights responded to William Hornaday's inquiries about private bison herds and wrote him that theirs now had 13.

Duncan: Molly, I think, deserves most of the credit for switching this buffalo killer, rancher, Indian fighter, into a guy who would start having some mercy.

She wanted him to take pity on some calves.

And I don't know if she thought, "Let's take pity on these calves and we'll start reviving the bison of North America," or just, "Let's take some pity on some of these calves who've lost their mother."

♪ Man: Buffalo Bill was a good fellow, and while he was no great shakes as a scout as he made the Eastern people believe, still we all liked him, and we had to hand it to him, because he was the only one that had brains enough to make that Wild West stuff pay money.

Teddy Blue Abbott.

Narrator: By 1889, Buffalo Bill Cody was the most famous American in the world.

To millions of people, he had become the dashing embodiment of a mythic West of bygone times.

As a young man, he had worked as a buffalo hunter for the railroads and a scout for the army during the Indian wars.

His exploits had been publicized-- and greatly exaggerated-- in scores of dime novels, some of which he turned into theatrical performances, always featuring Cody himself in the starring role.

♪ The stage eventually proved too confining and he launched "Buffalo Bill's Wild West," an outdoor show that promised "a year's visit West in 3 hours."

It was, Buffalo Bill said, "a noisy, rattling, gunpowder entertainment," featuring real cowboys and real Indians, Pony Express riders and Mexican vaqueros, and a series of vignettes supposedly demonstrating the history of the West-- and Cody's glorified role in it.

The Deadwood Stagecoach was attacked-- and saved by Buffalo Bill.

A wagon train was raided and saved by Buffalo Bill.

A settler's cabin was surrounded by Indians and saved by Buffalo Bill.

A re-enactment of the Battle of the Little Bighorn-- "Custer's Last Stand"-- ended with Buffalo Bill showing up while the words "TOO LATE" were displayed.

Each performance also included a stampede of buffalo and a mock hunt with Cody and his compatriots firing blank cartridges at the animals.

The crowds couldn't get enough of it.

♪ O'Brien: People loved these buffalo.

And he became the Great Plains' first roadside hustler.

Narrator: A million people attended his shows on Staten Island one summer.

Another million paid to see him that winter at Madison Square Garden, where 20 of Cody's bison perished from pneumonia.

He managed to replenish them from his ranch in Nebraska and, later, with 7 he bought from Molly and Charles Goodnight's growing herd.

Rinella: It's amazing how these transitions were so abrupt that a guy that kills 4,000 then becomes a guy, within a decade or two, becomes a guy who's trying desperately to find a couple in order to take them on the road to teach people about what they lost, "they" being him... the other day, right?

It's astounding.

♪ Narrator: In 1887, during a triumphant tour of Europe, Cody took his show to England for the celebration of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, bringing along 97 Native Americans and 18 buffalo.

Woman: "The Birmingham Gazette," November 4th, 1887.

Additional interest is attached to the buffaloes by the fact that they are almost the only survivors of what is nearly an extinct species.

According to Colonel Cody, there are not so many buffaloes on the whole American continent as there are in the exhibition.

Narrator: The Deadwood Stagecoach carried the kings of Denmark, Greece, Belgium, and Saxony, along with the Prince of Wales, while Cody himself drove the stage during a simulated Indian attack.

"I've held 4 kings," Buffalo Bill told a reporter, "but 4 kings and the Prince of Wales makes a royal flush such as no man ever held before."

♪ He became so famous that he would put up posters that showed some buffalo running.

In an oval cutout, in the center of the most prominent buffalo, was just his face.

And it would say, in bold letters, "I am coming."

He even had those in French.

Most Americans had never been to the Great Plains, of course.

That's still true.

But most Americans got their buffalo from Wild West or from Hornaday's glass box at the Smithsonian.

These played an incalculably large media role, public relations role, in building a constituency in the country to do something to save this creature from extinction.

♪ Man as Grinnell: The wild Indian exists no longer.

The game on which he lived has been destroyed; the country over which he roamed has been taken up; and his tribes, one by one, have been compelled to abandon the old nomadic life, and to settle down within the narrow confines of reservations.

♪ The magnitude of it is equaled only by the suddenness with which it has been wrought, and by its completeness.

George Bird Grinnell.

♪ Narrator: For the Native peoples of the Plains, the final decades of the 19th century were the most traumatic in their history.

Indian nations that had gone to war against White encroachments had been defeated by the United States Army and forced onto reservations.

So were tribes that had always remained peaceful.

Under law, Native Americans were not considered U.S. citizens, and to travel beyond a reservation boundary required government permission.

Woman: There was a system in place in the 19th century that was both enslaving people and it was also taking Indigenous people's land and landscape to feed kind of this capitalistic machine.

Uh, it was not inevitable.

It was planned.

Narrator: Well-meaning reformers in the East, calling themselves "Friends of the Indians," pushed Congress to enact a number of provisions intended to hasten Native Americans' assimilation into the White culture that now surrounded them.

Man: Our belongings were taken from us, even the little medicine bags our mothers had given us to protect us from harm.

Everything was placed in a heap and set afire.

Lone Wolf.

Narrator: Children as young as 5 years old were taken from their families and sent to boarding schools-- like one in Carlisle, Pennsylvania-- where they learned English, and were beaten if they spoke their native language.

All vestiges of their traditional culture were to be removed.

♪ "Education," said one reformer, "should seek the disintegration of the tribes.

"They should be educated, not as Indians, but as Americans."

♪ Duncan: "Kill the Indian, Save the Man."

And that was said by someone who was supposed to be a "Friend of the Indian."

The only way that the Native people could survive is to not be who they were.

"Kill the Indian, Save the Man" is kind of like, uh, save the bison, make it a cow.

It's saying they'll be allowed to exist as long as they don't stay what they are, as long as they become what we want them to be.

Even today, people say, "Well, it was inevitable, it was going to happen."

It was not inevitable.

♪ Narrator: In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes General Allotment Act.

It provided for each Indian family to be given 160 acres of farming land and 320 acres of grazing land on the reservation.

But then, all the remaining tribal land would be declared "surplus" and opened for Whites to purchase.

Tribal ownership-- and the tribes themselves-- were meant to simply disappear.

Before the Allotment Act, some 150 million acres remained in Native hands.

Within 20 years, 2/3 of their land had been taken.

Woman: The Allotment Act was one of the most devastating acts for Indian people.

They didn't understand private land ownership.

You didn't own land.

The land you were a part of; you used the land for the resources as you needed them.

The whole point of assimilating Indians, transforming Indians, was to open this area to settlement coming in.

That was the purpose then.

That was the government's goal.

♪ Narrator: The buffalo were gone, too.

Horse Capture, Jr.: Well, since the beginning, we and the buffalo have a fairly long history together.

Co-dependent, in a way.

Just like my people, their people suffered from "manifest destiny."

They were victims of genocide, ethnic cleansing, uh, westward expansion.

Shared history, all the way across.

Narrator: In the buffalo's place, the government supplied beef cows for the Indians to kill and eat.

At one Lakota Reservation, when the cattle were released into a large corral, the men mounted up and brought them down, just as they had brought down buffalo in the old days.

Eventually, the agent put an end to that, and built a slaughterhouse to kill and butcher the cattle.

The Lakotas burned the slaughterhouse down.

Man: We always say, "We're just like the buffalo."

They almost exterminated us, too.

And, when, when the zoos first started, what they'd do, they'd put buffalo in zoos.

And the old people would say, "What did they do to us?

They put us on reservations," and we couldn't get out of those reservations without a permit.

You know, the zoos kept the buffalo.

The White people kept us on reservations.

Same thing.

There are stories about old men going to those zoos and seeing buffalo.

You can imagine the fence and these old men crying and praying.

Pretty soon, those buffalo come over and they stand in front of him.

There was numerous stories like that, where the buffalo stand in front of him and, and look at him as he's praying and crying.

And then he has to go.

And the animals stay in that zoo.

They saw, by that point, an almost total destruction of all of the animals that were sacred to them.

It was not just the bison.

What happened to the elk?

What happened to the wolves?

What happened to the grizzlies?

It was sort of destruction after destruction after destruction.

Narrator: The elk and grizzly bears that survived could now be found only in the mountains.

Bighorn sheep disappeared from the Dakota Badlands.

Market hunters killed millions of antelope.

Herds of cattle and sheep now grazed where the buffalo had once roamed.

With the bison gone, the prairie itself began changing.

Millions of acres of soil were plowed for the first time.

Wheat, corn, and other crops replaced the native grasses.

Buffalo wallows--where vital rainwater had once pooled-- filled with sand.

On the southern Plains, in 1886, the Kiowa calendar showed a leafy tree above a lodge, signifying another summer without a Sun Dance, because no buffalo could be found to sacrifice for their ceremonies.

In 1887, they were able to hold their sacred ritual after they received one from the Goodnights.

♪ At the same time, the aging Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull had been touring with Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show, where he was paid to ride around the arena once during each performance, promoted as "the slayer of General Custer."

He also signed pictures of himself for the awestruck visitors who came to his tepee.

But after 4 months with Cody, Sitting Bull had seen enough of the White world.

He could not understand why beggars were ignored on the streets of big cities, and he gave much of his pay away to the hoboes and newsboys he met.

Back at the Standing Rock Reservation in Dakota Territory, he used the money he had left to provide feasts for his friends.

♪ Horse Capture, Jr.: Some of this is very hard to put into words.

But sometimes there'd be a certain amount of emptiness in a spot.

You can have this emptiness and you can't identify it.

It's only an emptiness, you know, and it's...maybe that would have been a part of it.

But, also, we got a lot of things that are--that are gone.

That are gone.

Narrator: In 1890, a summer drought killed whatever crops the Lakotas were trying to raise.

The government had already cut rations at every reservation by more than 20%.

Whooping cough and influenza spread among the hungry people, particularly the children.

♪ Then, word arrived that a new ceremony called the Ghost Dance was sweeping through many tribes of the West.

Preached by a Paiute medicine man and combining Christian as well as Indian elements, it offered dispirited Native Americans hope.

Man: My brothers, I bring you word from your fathers, the ghosts, that they are marching now to join you, led by the Messiah who came once to live on Earth with the White man, but was killed by them.

I bring to you the promise of the day in which there will be no White man to lay his hand on the bridle of an Indian's horse; when the red men of the prairie will rule the world.

Wovoka.

♪ Narrator: Wovoka's prophecy required men and women to purify themselves, give up alcohol, and forswear violence.

Then, they were to dance in a large circle, singing and calling upon the spirits of their ancestors.

If they did, the Ghost Dancers believed, the Whites would vanish and the buffalo would cover the Plains again.

"Give me my arrows," they sang as they danced.

"The buffalo are coming, the buffalo are coming."

♪ Though he lived in New York City, the naturalist and writer George Bird Grinnell spent parts of every year living among the Pawnee, Blackfeet, and Cheyenne, listening to their stories, studying their religion, learning their history.

In the fall of 1890, he watched the Cheyenne hold a Ghost Dance.

Grinnell understood the appeal of its message.

"This is only what any of us will do," he wrote, "if we get hungry."

♪ In the Lakotas' adaptation of the ceremony, Ghost Dancers wore special shirts, said to be impervious to the White man's bullets.

Government agents became alarmed, fearing an uprising was imminent.

As a precautionary measure, Indian police at the Standing Rock Reservation were ordered to arrest the most prominent Lakota chief-- Sitting Bull.

When some of his followers resisted, a fight broke out.

Both sides began firing and a dozen people were killed.

Sitting Bull was one of them.

♪ Several hundred Lakotas, flying a white flag, headed toward the Black Hills, and planned to turn themselves over to the U.S. Army to settle things peaceably before more blood was shed.

They encamped one night at a creek called Wounded Knee.

♪ The next morning, December 29th, 1890, soldiers armed with 4 devastating Hotchkiss guns encircled the camp and began confiscating the Indians' weapons.

[Gunshot] Someone's gun went off.

[Gunfire] The soldiers opened fire.

When the shooting stopped, more than 250 Lakotas-- most of them women and children--were dead.

So were 25 soldiers.

Horse Capture, Jr.: What was they trying to do?

They was trying to dance their ways back.

They were praying.

They tried to dance the buffalo back.

You know?

And they paid with their lives.

♪ Man as Grinnell: The most shameful chapter of American history is that in which is recorded the account of our dealings with the Indians.

The story of our government's relations with this race is an unbroken narrative of injustice, fraud, and robbery.

We are too apt to forget that these people are humans like ourselves, that they are fathers and mothers, husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, men and women with emotions and passions like our own.

George Bird Grinnell.

♪ Narrator: Growing up in New York City, George Bird Grinnell had been a student of Lucy Audubon, the widow of the famous ornithologist and painter.

Among the things she taught the boy was how to observe and appreciate the natural world.

Man: But, even more significantly, she teaches him about an ethic that was important to her that she called "self-denial."

And what she really meant by self-denial was the notion that you would, uh, you would think about future generations, that you would not do things that you might want to do in deference to thinking about, uh, how your children and grandchildren might live one day.

And that ethic runs almost directly counter to the prevailing norms of the day.

Narrator: As the editor of "Forest and Stream" magazine, Grinnell put Lucy Audubon's lessons to work.

He railed against the hat-making industry, which had created a fashion frenzy for the colorful plumes of birds in the Everglades, threatening the survival of egrets and ibises.

[Gunshot] And he decried the market hunters who were supplying restaurants with the meat of passenger pigeons, driving a bird that once existed in the billions toward oblivion.

To help him carry on the fight against this commercial destruction of bird life, Grinnell founded an organization named in honor of his mentor and her husband: the Audubon Society.

But he never lost his focus on the American buffalo.

♪ Punke: Every saloon in America wants to have a stuffed buffalo head to hang on the wall.

And the market for buffalo heads goes through the roof.

And, uh, what used to be a $4.00 shot if you killed a buffalo and could sell its hide becomes a $500 shot.

And the response to that is poachers descend upon these few places where there still are buffalo remaining and try to kill them.

Narrator: By 1894, the last surviving herd of free-ranging bison in America could be found in Yellowstone National Park.

But the superintendent reported that poachers had killed 114 of the 200 William T. Hornaday had estimated were there only 4 years earlier.

The Army was responsible for stopping poachers in Yellowstone and for enforcing regulations against vandalizing the geyser formations, but the park existed in a legal no-man's land, with no federal law giving the soldiers clear authority to prosecute offenders.

Their only recourse was a warning, or in the most serious cases, temporary expulsion from the park.

No one understood the threat to Yellowstone and its wildlife more keenly than George Bird Grinnell.

Punke: He knows that it's this vast place.

He knows that there are a handful of wild buffalo who are still there because they've been far enough away from the railroads that they still survive.

Grinnell realizes that this is the buffalo's, that Yellowstone is the buffalo's last chance.

[Gunfire] Narrator: On March 13th, 1894, two troopers out on patrol in a remote corner of Yellowstone heard shots in the distance.

They hurried in that direction and soon came across several buffalo carcasses.

A man was hunched over one of them, so busily skinning it that he didn't realize anyone was there until a soldier was beside him with a drawn gun.

The poacher was Edgar Howell, who had been killing Yellowstone's bison for years.

As luck would have it, a reporter named Emerson Hough, on assignment for Grinnell's "Forest and Stream" magazine, was also in the park-- with a photographer-- to write an article about Yellowstone in the winter.

When the poacher bragged that the worst punishment he could receive for his crime was expulsion from the park, Hough realized he had stumbled onto a great story and quickly telegraphed it to Grinnell in New York City.

Grinnell knew just what to do with it-- and began to generate a public outcry for Congressional action through a series of stories, along with photographs that included soldiers posing with 9 buffalo heads that Howell had not yet hauled out of the park.

Punke: And it's a political lightning bolt in Washington.

In his editorials, Grinnell was very good at explaining that Yellowstone National Park belongs to all Americans.

So that when someone, when a poacher, is stealing from Yellowstone National Park, he's stealing from you.

Narrator: In Washington, Grinnell's friend Theodore Roosevelt, now a Civil Service Commissioner, sprang into action.

He stalked the corridors of the Capitol, lobbying for a bill that would institute fines of up to $1,000 and jail sentences of up to two years for offenders.

On May 7th, 1894-- less than two months after Howell's capture-- President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law, authorizing regulations that would protect the park, its geysers, and its wildlife-- at least on paper.

♪ Man as Hornaday: The nearer the species approaches to complete extermination, the more eagerly are the wretched fugitives pursued to the death whenever found.

Western hunters are striving for the questionable honor of killing the last buffalo.

At least 8 or 10 buffaloes of pure breed should be secured very soon by the National Zoo and cared for with special reference in keeping the breed absolutely pure.

William T. Hornaday.

Narrator: When the new National Zoo opened in 1891, William T. Hornaday was no longer at the Smithsonian.

He was living in Buffalo, New York, working for a real estate company.

Disagreements with his old colleagues in Washington had prompted him to abruptly resign.

Nijhuis: He was quite notoriously temperamental, irritable, difficult to get along with.

But, at the same time, very charismatic, a great speaker, a great public advocate.

He was genuinely passionate about the long-term survival of the bison.

Narrator: In early 1896, he received an invitation from the newly formed New York Zoological Society, asking whether he would like to help them create in the city what they envisioned as the world's largest zoo.

Hornaday readily accepted the job to become its first director, design it, and find the best location for it.

He found that location in the Bronx, and for the next 3 years personally supervised every detail of the construction-- from deciding which trees could be cut down to what animals would be showcased.

When it opened in late 1899, the Bronx Zoo was an immediate success, soon attracting more than a million visitors a year.

Many of them seemed particularly fascinated by the small buffalo herd, which in a few years would grow to 26.

They included bison that had originally been captured by Buffalo Jones and 3 bulls and a cow from Charles and Molly Goodnight's ranch.

Hornaday was proud that he could now display live buffalo-- instead of stuffed ones, as he had at the Smithsonian-- to millions of Americans, who, he hoped, would join his newfound crusade for preserving wildlife.

♪ But he also worried that a few bison saved in zoos, on private ranches--or even in the small herd under the uncertain protection of Yellowstone National Park-- were not enough.

"The only way to ensure the perpetuation of the bison species permanently," Hornaday said, "is to create large herds," preferably in their native homes in the West.

The idea that citizens of the United States had driven this species extinct was--was offensive to him, was an outrage to him.

But it was also tied up with his strong sense of racial superiority.

Narrator: One of the most prominent founders of the Bronx Zoo was Madison Grant, a widely admired conservationist, who had led the effort to save the Redwoods in California.

He was also a leading proponent of a new pseudo-science called eugenics.

It falsely claimed, with no evidence, that human beings could be separated into a rigid, immutable hierarchy based not only on the color of their skin, but the so-called "purity" of their ancestry.

At the top were certain tall, blue-eyed white Protestants-- like Grant-- the real Americans, he thought, who were the rightful inheritors and now stewards of the continent.

Everyone else was catalogued in a descending order of genetic inferiority.

Madison Grant would eventually put his racist theories in a book, "The Passing of the Great Race."

Theodore Roosevelt and William T. Hornaday subscribed to many of the book's views.

Nijhuis: Hornaday was stridently anti-Catholic, stridently anti-immigrant.

He blamed Italian Americans and African Americans, without evidence, for the decline of songbirds in the American South.

West: These racists, these White supremacists, were only one group of those who were saving the bison.

But they were sure there.

They were sure there.

Narrator: More than 1,500 miles west of the Bronx Zoo, the two biggest bison herds in the nation were being managed by several families on two reservations on the northern Plains.

In South Dakota, Frederick Dupuis, a French-Canadian fur trader, had married Good Elk Woman, a Minniconjou Lakota, and established a ranch on the Cheyenne River Reservation, where they raised 9 children.

In the early 1880s, just as the hide hunters were finishing their slaughter, the Dupuis had captured 4 bison calves and began raising them on the ranch.

By the time Frederick died in 1898, their herd numbered nearly 80 buffaloes.

A Scottish immigrant, James Philip-- whose wife Sarah was also from the Cheyenne River Reservation-- bought the herd and moved it to 6,000 acres of rangeland along the Missouri River, a few miles north of Fort Pierre.

O'Brien: Dupuis, and Scotty Philip, these guys must have had either very tough wives, or they were really in love because they were the ones that drove these two hard-ass cowboys to go out and take care of these buffalo.

♪ Narrator: One of Scotty Philip's buffaloes, named Pierre, became an international celebrity when it took part in what was called the "Bull Fight of the Century" in the Plaza de Toros in Juarez, Mexico.

When a spirited Mexican bull was released and immediately attacked him, Pierre pivoted quickly and the two animals butted heads, bringing the Mexican bull to its knees.

After several more attempts-- each with the same result-- it began circling the arena, looking for a gate to be let out.

In quick succession, 3 more bulls were sent in to attack Pierre.

Refusing to move, he knocked them down one after another.

Then he stretched out in the sun and took a nap.

A week later, a younger bison bull, Pierre Jr., was scheduled to face a matador.

But the provincial governor called off the spectacle, not willing to risk losing Juarez's best bull fighter.

Narrator: By the early 1900s, the largest herd of buffalo-- including 300 bulls, cows, and calves-- grazed on the Flathead Reservation in northwestern Montana, home of the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreille people.

Accounts of that herd's origins differ, but according to tribal oral history, sometime in the 1870s, a young man named Latatí traveled east over the Rocky Mountains to the buffalo plains and brought back 6 calves.

♪ The herd grew, and in the 1880s, two ranchers on the reservation, Charles Allard and Michel Pablo, had bought them.

Charles Allard was part Indian and married to Louise, a Pend d'Oreille woman.

Michel Pablo was born on the Blackfeet Reservation and married to Agathe, also a Pend d'Oreille.

Pablo: My great-great- grandfather, Michel Pablo, was the son of, they called him "Old Man Pablo," and Otter Woman, who was Piegan Blackfeet.

So, he was half Blackfeet, half Spaniard, or Mexican.

He saw the buffalo at their prime.

I mean, he saw the buffalo when there were lots of them.

Narrator: The Pablo-Allard herd flourished on the reservation's lush pastures just west of Montana's Mission Mountains.

With 50 calves born each year, their herd kept expanding.

When Allard died in 1896, his family began slowly selling off his bison to various buyers.

But Pablo stayed put-- and his buffalo soon numbered in the hundreds.

Pablo: It was much more than a business for him.

He was a visionary.

He...he knew we needed the buffalo on this Earth to survive as people.

Not just Indians; we need the buffalo to survive.

We need that spirit.

Narrator: Michel Pablo was now in charge of more buffalo than anyone else in the nation-- including the federal government.

Despite the law passed in 1894 to protect them, the number of wild and free-ranging bison in Yellowstone National Park had dwindled to less than two dozen.

♪ Lapier: Part of the motivation for the Americans who were interested in preserving bison at the turn of the last century was not to return them to the wild.

It was actually to preserve them so that people could see them, almost as a zoo-type species.

There was no interest, at that time, in creating large landscapes where bison could be a wild species.

There was an interest in creating small landscapes, where bison could be preserved, where people could go see them.

Narrator: Of all the unlikely places where a herd of buffalo could be found in the United States, none was more unlikely than the Blue Mountain Forest Reservation in western New Hampshire.

Covering 24,000 acres and surrounded by an 8 1/2-foot-high fence, it was the private retreat of a millionaire banker, Austin Corbin.

For years, he had stocked his estate with exotic game animals-- caribou, Himalayan goats, and wild boar from Germany's Black Forest.

Corbin had also purchased 10 bison for $1,000 each from Buffalo Jones in Kansas.

By 1904, Corbin's heirs owned a herd of 160.

That same year, the family agreed to provide an unoccupied house on the property to an eccentric nature writer from Boston named Ernest Harold Baynes, who was scratching out a living by submitting stories to newspapers and magazines-- accompanied by photographs taken by his wife Louise-- about birds and snapping turtles, squirrels, and opossums.

At Blue Mountain, Baynes expanded his work-- and Louise kept her camera ready to record it.

[Camera's shutter clicking] His wife Louise would take pictures of him, hundreds of pictures of him, him feeding a bird off of his lip, or a finger.

They had, uh, wolf pups that they named "Death" and "Dauntless."

He had a pet red fox.

He adopted this wild boar and took it on the lecture tour until it grew into a real Black Forest wild boar with tusks and kind of a mean temperament.

♪ At the same time, he saw this as part of a way to reach people.

He didn't think of wild animals, I don't believe, as pets.

He believed that the way to capture Americans' attention to the importance of habitat, and other things for wild animals, rather than just slaughtering them, was to engage people this way.

Narrator: What captivated Baynes the most was the buffalo herd roaming across the nearby pastures and forests.

In his first encounter with them, they galloped away, except for an immense bull, who steadfastly refused to move.

Man as Baynes: Perhaps never did I feel so much ashamed in the presence of any animal as when, standing face to face with that magnificent creature, I thought of the wrongs his race had suffered at the hands of mine.

♪ Narrator: With the help of the preserve's gamekeeper, he brought 3 calves back to his barnyard-- two young bulls he named War Whoop and Tomahawk, and a female he called Sacajawea.

He fed them cow's milk from a baby bottle-- and watched them grow.

Man as Baynes: I decided that the time had come to teach them what they could do for man in order that he in turn might learn what he could do with them.

Narrator: When they were 5 months old, he took them to the Sullivan County Fair, where they created a sensation-- pulling the stone sled that carried a barrel of apples, then a wagon with a load of hay.

For a grand finale, they took him and a small cart around the fair's race track at full speed.

By the time War Whoop and Tomahawk were 2 1/2 years old, they were famous.

Baynes brought them to the Central Maine Fair, where a young farmer accepted the challenge for a race between his steer and War Whoop.

"The result," Baynes wrote, "was not in doubt for a moment."

Man as Baynes: This was the last appearance of my calves.

They were trained to awaken interest in the American bison... and they had done their share.

♪ Narrator: Because of the costs involved, the Corbin family began to talk about getting rid of their buffalo herd.

To save the bison as a species, Baynes now believed a national organization should be created and the federal government needed to establish several more herds.

In Walpole, New Hampshire, Baynes met with Professor Franklin W. Hooper, director of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, to discuss the idea.

Hooper encouraged him to write to a number of prominent Americans, including the enthusiastic hunter who had now become an ardent conservationist and the President of the United States--Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt responded immediately and promised to address the issue in his annual message to Congress.

Man as Roosevelt: To the Senate and House of Representatives...

I desire to urge upon the Congress the importance of authorizing the President to set aside certain portions of the forest reserves as game refuges for the preservation of the bison.

We owe it to future generations to keep alive the noble and beautiful creatures, which by their presence add such distinctive character to the American wilderness.

Narrator: Baynes had also been corresponding with William T. Hornaday, who shared his belief that multiple federal herds were crucial.

The close confines of zoos, the uncertainties of private herds, and concerns about crossbreeding with cattle provided no guarantee that any buffalo would still exist in another generation.

Rinella: We got to the era when you could just count them up, right, there were so few here and there.

It was perfectly plausible that you could have a disease break out and it would kill half of the animals left in the country.

Half the animals left in the world.

A lightning strike could have walked away with 10%, 25% of the known animals.

[Thunder] There was a real vulnerability.

In some of the surviving bison herds that make it into the 20th century, there are a dozen, or fewer, animals.

And there's one dominant bull who may be siring all of the animals.

And, so, it's a problem with inbreeding.

'Cause there's just not enough genetic diversity among them.

Zoos weren't big enough.

Private ownership was too tenuous.

What you needed was bigger places; and, most importantly, you had to have the stability and perpetuity of government control.

♪ Narrator: By 1904, the most imposing home on the Comanche Reservation in Oklahoma, called the Star House, was a two-story structure with spacious wrap-around porches.

Inside, the home boasted 10-foot ceilings, a large dining room with formal wallpaper, and a wood-burning stove, and plenty of bedrooms for a big family.

Its proud owner was Quanah Parker, the leader of the Quahada band of Comanches.

The story goes that Quanah had met a military general who had 3 stars on his uniform.

And Quanah said, "I deserve more than that," and more than doubled that with the stars on the roof of the "Star House."

Narrator: Quanah and his Quahadas had been the last to surrender on the Southern Plains and settle on a reservation in 1875.

But now, no Comanche was more committed to helping his people adapt to reservation life than Quanah Parker-- who had added his mother's last name to his own as a sign of respect for her memory.

Man: He was a natural leader.

In one century, he was a warrior; in the other century, he, he was-- led us into the new world.

He was preparing us for that.

Trying to live in two worlds is a very common thing among Native American people.

He was rather successful at it, I think.

But he must have lived in turmoil some of the time, then, wondering which way to go, which direction to take at this fork in the road that he had been given.

Tahmahkera: He would adapt and adapt, time and again, to do what was best for his people.

He saw that certain eras were fading, but he never stopped being Comanche.

♪ Narrator: He used the same skills when dealing with White officials and businessmen-- negotiating a deal that permitted cattle drives across Indian lands in exchange for taxes on each wagon and each cow.

Eventually, he built his own cattle herd of 500 head on what was called the "Quanah Pasture," and he ran a 150-acre farm with crops and 200 hogs, tended by a hired White man.

At his big house, he hosted a constant stream of prominent visitors.

With them, he never talked about his time as a warrior, preferring to win them over with his easy manner and ready sense of humor.

On some things, Quanah Parker never compromised.

He always wore his hair long and in braids, even when wearing a business suit.

Despite strict government rules outlawing polygamy on reservations, he had 8 wives, with whom he fathered 24 children.

And he openly advocated the use of peyote in religious ceremonies, though it, too, was banned by law.

"The White man goes into his church house and talks about Jesus," he explained about the use of the hallucinogen, "but the Indian goes into his tepee and talks to Jesus."

[Band playing "Hail to the Chief"] Narrator: On March 4th, 1905, Theodore Roosevelt was inaugurated for his first full term as President.

Riding in the parade were 6 Native American leaders from different western tribes, including Geronimo of the Apache and Quanah Parker of the Comanche.

Invited to a private reception at the White House, Quanah learned that the President was planning a hunting trip to Oklahoma in April and offered to return Roosevelt's hospitality.

♪ When the President's train arrived in Frederick, Oklahoma, Quanah was among the 3,000 people gathered to welcome him.

♪ Then, the two men and a small group spent several days camping and hunting coyotes-- getting to know one another better.

Flores: We know that Roosevelt does not have a favorable impression of Indigenous people anywhere on the planet.

He has the idea that Indigenous people represent an earlier form of humans.

Duncan: Roosevelt's time with Quanah, it didn't totally change his view of Native people.

He had written some really shameful things about his opinion of Indians.

I don't know if it-- if it's true friendship, or if it's just an understanding by two old warriors that we see thing--the world differently.

Narrator: After the hunt, Quanah hosted the president for lunch at his house.

Tahmahkera: It's during this time, where Quanah can talk one-on-one with Roosevelt, to be able to help further instill these ideas about the importance of not just preserving the relatively few buffalo left, but being able to revitalize herds.

Narrator: The president spent the night sleeping on one of the porches.

Before he left, he presented Quanah with a small porcelain cup-- and then some news.

Congress, he said, had given him authority to create a preserve for large game animals-- especially buffaloes-- and his trip to Oklahoma had convinced him that the Wichita Mountains would be a perfect location.

On June 2nd, 1905, Roosevelt signed an executive order designating 60,000 acres of national forest as the Wichita Forest and Game Preserve-- the first of its kind.

It was on land that had been taken from the Comanches years earlier.

♪ 6 months later, in the reception room of the Bronx Zoo's Lion House, the first meeting of a new organization, the American Bison Society, took place.

It was something Ernest Harold Baynes of New Hampshire had been advocating for for more than a year.

"The objects of this Society," the group declared, "shall be the permanent preservation and increase of the American bison."

William T. Hornaday was elected as its president, Baynes to serve as its secretary.

Theodore Roosevelt had agreed to lend his name as honorary president.

Roosevelt's real presidency-- of the United States-- was dedicated to his belief that a vigorous federal government was essential, the only force capable of combatting the immense power of the robber barons, monopolies, and trusts that controlled the nation's railroads, banking, oil, timber, and mining interests.

He also championed the cause of conservation as no president had ever done: creating national parks, national forests, national monuments, national bird sanctuaries, and wildlife refuges.

"When I hear of the destruction of a species," he now said, "I feel just as if the works of some great writer had perished."

Meanwhile, William Hornaday successfully lobbied Congress to put up $15,000 for fencing and buildings at the Wichita Mountains preserve-- after he promised that the Bronx Zoo would donate 15 of their pure-bred bison to provide the seed stock.

♪ On October 11th, 1907, everything was ready.

Hornaday had personally designed special crates for each animal-- 9 cows and 6 bulls-- for their 1,500-mile journey to Oklahoma.

At the Fordham railroad station in the Bronx, they were loaded onto two freight cars usually reserved for transporting expensive thoroughbreds.

They have to move them, not from the last wild bastions, you know, the last canyon, um, hideouts of the animals in the American West.

They have to move them from the Bronx Zoo back to the American West.

Not only that, by rail.

So, all this time we've been taking hides and tongues, and shipping it in trains to be consumed in the East.

And people in the East are taking trains out to shoot the animals out the windows and just leave them to rot on the Prairie.

But, all of a sudden, now we're at this point where we have a small herd of them in the biggest city on the continent... and they put 15 on a train and drive them back out West.

Duncan: This had to be the most extraordinary bison migration in the history of North America.

They get on a train in New York City to head home to the Great Plains, to the Wichita Mountains, which were the sacred place where some people believed they had first emerged onto the surface of the Earth, and where others had believed this is where they went to hide until it was time to return again.

Narrator: 7 days later, they arrived at the train station in Cache, Oklahoma, and were taken 12 miles by wagon to a holding corral, before their release into the preserve.

♪ Among the spectators awaiting the bison was Quanah Parker--along with other Comanches and Kiowas, some of them old enough to remember the days when buffalo covered the prairie-- some of them children who had only heard about buffalo in stories.

I'd like to think there is a calling out to the buffalo, "tasiwóo", "tasiwóo."

Calling out to those buffalo and being able to try to continue, being able to reestablish some kind of relationship between Comanches and those who had, for generations, provided so much for us.

What must have gone on in their minds, you know, in their--in their blood memory, they had to be, uh, amazed and probably joyful.

Um...also, a kind of remorse, a kind of sadness.

Quanah Parker cried when he saw the buffalo return.

I can imagine that.

You know, I think that could be true, not only of him, but of many other people who witnessed this miracle of return.

♪ Woman: One young woman got up, very early in the morning... Narrator: For nearly two generations, following the destruction wrought by the hide hunters in the early 1870s, the Kiowas had passed along a legend told by Old Lady Horse about the last buffalo herd.

Woman: ...last buffalo herd appear like a spirit dream.

Narrator: They had walked, she said, into Mount Scott-- the sacred place from which, the tribe believed, the animals had first emerged onto the Great Plains in the age before people.

Woman: Into this world of beauty, the buffalo walked.

Narrator: After some time in their holding corral, the 15 buffalo from the Bronx Zoo were set loose, free to wander in their new old home, within sight of Mount Scott.

♪ Momaday: Old Lady Horse.

I like to think of her there.

If she had seen their return, her sense of the sacred would have been realized at that moment as a high point in her life.

That makes the story whole.

♪ Narrator: Less than a month after the buffalo's arrival, two calves were born.

Within 6 years, the herd would double in size.

♪ Isenberg: The people who are interested in preserving the bison, the American Bison Society and associated groups, are not at all interested in preserving bison on behalf of Indigenous people in the Great Plains.

In fact, in many ways, the preservation of the bison comes at the expense of Indigenous people.

The notable bison preserves, these are created when what had been very large reservations were diminished in size through this complicated process known as "Allotment."

So, ironically, the killing of the bison by hide hunters in the 1880s had come at the expense of Native people, and the preservation of the bison in the early 20th century also comes at the expense of Native people.

Narrator: In Montana, much of the Flathead Reservation had been broken up into small parcels through the Dawes Allotment Act.

The remainder was declared "surplus" and was about to be opened to homesteaders.

Michel Pablo realized his buffalo pastures would be divided up and sold in the impending land rush.

Pablo: You can't run 600 head of buffalo on 160 acres.

So, Michel saw the finger of doom for his buffalo.

Narrator: Pablo offered to sell his herd to the United States.

President Roosevelt favored the proposal; George Bird Grinnell and others endorsed it.

But Congress refused to appropriate any money.

Pablo: He was so hopeful that the buffalo would stay that when he had to sell them, his spirit was broken.

He was devastated.

Narrator: The Canadian government, looking to create Buffalo National Park in Alberta, jumped at the opportunity and bought the entire herd.

With Joe Allard, the son of his late partner, Pablo recruited some local cowboys and began to round up the buffalo in the summer of 1907.

♪ Pablo had estimated it would take them two years to gather his herd into corrals and get them onto freight trains for shipment to Canada.

It took more than 5.

Instead of 350 bison, to his surprise it turned out he had nearly twice as many-- and they often proved unwilling to leave their home range.

♪ Woman: Have you ever tried to herd buffalo?

[Laughs] It's not easy to herd buffalo.

They are astonishing in their athleticism and their power.

But one thing they don't do well is, like, take orders.

So, if somebody's trying to round them up and force them into little carts, that's not an easy thing.

You don't mess with a 2,000-pound animal and survive.

Narrator: One of the participants at two of the roundups was the painter and former cowboy Charles M. Russell.

He was world famous for creating works that portrayed a West that seemed to be a fading memory-- symbolized by the buffalo skull he attached to every painting, next to his name.

For Russell, the chance to take part in another roundup-- this time with buffaloes-- proved irresistible.

He rode with the cowboys, told stories of the old days around the campfire-- and sketched watercolors to his heart's content, sometimes adding them to illustrate letters he sent to friends.

Ultimately, Michel Pablo would deliver more than 670 bison to Canada.

♪ But news of the sale had created a national uproar.

"President Roosevelt may easily be imagined stamping his feet and grinding his teeth," a Denver newspaper reported, "when he hears that his cherished ambition "to secure for American national parks "the famous herd belonging to Michel Pablo "has been defeated by energetic officials of the Canadian government."

The American Bison Society used all the negative publicity to push Congress into appropriating $40,000 to purchase and fence 29 square miles of land in the Flathead Reservation for a new buffalo preserve-- not far from where Pablo's herd had once grazed.

Pablo: How dumb can this be?

What an insult.

You had the chance to buy this premier herd, and you make a buffalo, bison range, um, right in the midst of where they were?

It doesn't make any sense.

Narrator: The Bison Society then launched a private campaign to raise $10,000 to buy more buffalo.

Since some of Pablo's herd hadn't yet been rounded up for shipment to Canada, many people hoped the Bison Society could buy them from him.

But no deal could be arranged.

Pablo said he wouldn't break his agreement with the Canadians, which infuriated William T. Hornaday.

He would never, Hornaday wrote a colleague, "ask favors of a half-breed Mexican-Flathead."

The reservation agent told George Bird Grinnell that the problem was what he called Hornaday's "unpardonable sin" of racial hostility.

♪ In the end, the Bison Society purchased 34 buffalo from a family in Kalispell, Montana, who had bought part of the Allard herd back in 1902.

The Goodnights in Texas donated two of their buffalo.

The Corbin family in New Hampshire gave 3 from their herd.

On October 17th, 1909, the animals were released to graze on the National Bison Range.

The United States had 3 federal herds under protection-- in Yellowstone National Park, the Wichita Mountains, and now western Montana.

75 of Michel Pablo's buffalo had eluded capture for Canada, and for a while they grazed outside the new preserve's fences-- sometimes creating problems for homesteaders in the region.

The State of Montana claimed jurisdiction over what came to be called the "outlaw herd," but declined any suggestions to try and move them inside the new federal bison range.

[Gunshot] Poachers went to work, eventually killing them all.

Within the next 6 years, more protected herds were established-- at Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota's Black Hills and at nearby Custer State Park.

At Fort Niobrara in Nebraska.

Even one in a national forest near Asheville, North Carolina.

In the Texas Panhandle, Molly and Charles Goodnight called for a Palo Duro Canyon National Forest Reserve and Park.

Legislation to create it was introduced in Congress 3 times.

Each time, the bill was turned down, because the land was not already federally owned and purchasing it was considered too expensive.

Over time, the old Indian fighter Charlie Goodnight had become friendly with a number of Native tribes, and he helped Quanah Parker in his efforts to have his mother and little sister reburied on the Comanche Reservation in Oklahoma-- not far from where the Wichita Mountains herd now grazed.

In thanks, Quanah presented Goodnight with a lance he had used in the raid against the hide hunters at Adobe Walls back in 1874.

In 1911, he wrote to Goodnight saying he planned to bring 50 other Comanches with him to Charlie's ranch to "see your buffalo and make these old Indians glad."

But Quanah Parker never made it.

He died a month later-- and was buried, as he had wanted, next to his mother and sister.

♪ 5 years later, Goodnight invited some Kiowas to his ranch.

They came to help make a film that would capture scenes from the West the 80-year-old Goodnight remembered-- more authentic, he hoped, than the romanticized Westerns playing in movie theaters across the nation.

The highlight was a buffalo hunt-- with real Indians riding after a real buffalo herd, and finally bringing one down with bows and arrows.